10 things you might not know about Sultan Suleiman I

Portrait of Sultan Suleiman I by Italian painter Titian, edited by Büşra Öztürk

Portrait of Sultan Suleiman I by Italian painter Titian, edited by Büşra Öztürk

Sultan Suleiman I inherited the throne of the Ottoman Empire at the age of 26. He was the only son of Selim I, who conquered Mecca, Medina, Jerusalem and Alexandria.

Suleiman I, (1494 – 1566), was known as ‘The Magnificent’ during his reign, because of his conquests and renowned wisdom. He was also known as ‘The Lawgiver’, although this epithet may date from the early 18th century. Under his administration, from 1520 until his death in 1566, the Ottoman Empire ruled more than 25 million people across Southern Europe and North Africa.

Suleiman The Magnificent had great ideals when he ascended the throne as a young man. He wanted to realise the goals of his great grandfather, Sultan Mehmed II. The basis of these goals was to establish a state comparable with the Roman Empire.

Suleiman began his reign with campaigns against the Christian strongholds in the Mediterranean region and central Europe. In 1521 he conquered Belgrade, then the island of Rhodes in 1522–23. In August 1526, the Janissaries, (the elite infantry of the Ottoman Empire), won a decisive victory against the Hungarian army at the Battle of Mohacs. Thus, the army of Sultan Suleiman found themselves outside the gates of Vienna.

Battle of Mohacs, 1526

Battle of Mohacs, 1526

Suleiman annexed much of the Middle East in his conflict with the Safavids, (a dynastic family that ruled over modern-day Iran) as well as large areas of North Africa, as far west as Algeria. Under his rule, the Ottoman fleet dominated the seas from the Mediterranean to the Red Sea and through the Persian Gulf.

The achievements of Suleiman the Magnificent had made him an important force in European politics. He followed the political and cultural developments in Europe closely. Thus, an alliance was formed with King Francis I of France against the Habsburg Monarchy. When Hungary fell, (the buffer state between Suleiman and Western Europe) the Ottoman Empire and the Holy Roman Empire became neighbours. This triggered a rivalry that would last for decades. Suleiman I and the Holy Roman emperor, Charles V, entered a struggle for supremacy in the Mediterranean.

Map of the Ottoman Empire, 1570, Everett Collection Historical via Alamy

Map of the Ottoman Empire, 1570, Everett Collection Historical via Alamy

10 things you might not know about Sultan Suleiman I

1. Suleiman’s army was stopped at the gates of Vienna. In the autumn of 1530 his forces laid siege to the great city. This was to be the Ottoman Empire’s most ambitious expedition. With a reinforced garrison of 16,000 men, the Austrians inflicted the first defeat on Suleiman, sowing the seeds of a bitter Ottoman–Habsburg rivalry that lasted until the 20th century. His second attempt to conquer Vienna also failed, in 1532, as Ottoman forces were delayed by the siege of Güns and failed to reach the city. In both cases the Ottoman army was plagued by bad weather, forcing them to leave behind essential siege equipment. They were also restricted by overstretched supply lines. The Ottoman forces retreated from the outskirts of Vienna, but they would return again 150 years later.

2. As a young man, Suleiman befriended Pargali Ibrahim, a Greek slave, who later became one of his most trusted advisers. The two men had met at the Topkapi Palace, when Suleiman was still a prince. They studied together and were inseparable friends and also lovers. Ibrahim was promoted to the position of ‘Grand Vizier’, (the highest bureaucratic level of the state). He was known as ‘Pargali Ibrahim’ because he was born in the Greek town of Parga. Ibrahim had a Western mindset and had huge influence over the young Sultan. However, in later years, Ibrahim eventually fell from grace, following prolonged disagreements with the Sultan and his beloved wife, Hurrem Sultan. Suleiman recruited assassins and ordered them to strangle Ibrahim in his sleep.

3. Suleiman was infatuated with Hurrem Sultan, a harem girl from Ruthenia, then part of Poland. Western diplomats called her ‘Roxelana’, or ‘Russelazie’, referring to her Ruthenian origins. The daughter of an Orthodox priest, she was captured by Tatars from Crimea, sold as a slave in Constantinople, and eventually rose through the ranks of the Harem to become Suleiman’s favourite. Hurrem, a former concubine, became the legal wife of the Sultan, much to the astonishment of the observers in the palace. He also allowed Hurrem Sultan to remain with him at court for the rest of her life, breaking another tradition. Normally when imperial heirs came of age, they would be dismissed, along with the imperial concubine who bore them, to govern remote provinces of the Empire.

4. Suleiman was a poet. He wrote under the pen name, Muhibbi, and composed this poem for Hurrem Sultan:

Throne of my lonely niche, my wealth, my love, my moonlight.

My most sincere friend, my confidant, my very existence, my Sultan, my one and only love.

The most beautiful among the beautiful…

My springtime, my merry faced love, my daytime, my sweetheart, laughing leaf …

My plants, my sweet, my rose, the one only who does not distress me in this room …

My Istanbul, my karaman, the earth of my Anatolia

My Badakhshan, my Baghdad and Khorasan

My woman of the beautiful hair, my love of the slanted brow, my love of eyes full of misery

I’ll sing your praises always

I, lover of the tormented heart, Muhibbi with eyes full of tears, I am happy.

Portrait of Roxelana, titled Rossa Solymannı Vxor

Portrait of Roxelana, titled Rossa Solymannı Vxor

5. This is Suleiman’s most famous verse:

The people think of wealth and power as the greatest fate,

But in this world a spell of health is the best state.

What men call sovereignty is a worldly strife and constant war;

Worship of God is the highest throne, the happiest of all estates.

6. Wives and concubines: Suleiman had two known consorts, although, in total there were 17 women in his harem when he was a Şehzade, (a prince with imperial blood) Mahidevran Hatun, a Circassian, or Albanian concubine, was Suleiman’s first wife. Suleiman’s concubine and later legal wife, (married in 1533, or 1534) was Hurrem.

7. He had 8 sons and 5 daughters in total, although 4 of his progeny died during childhood.

8. White Tulips: Suleiman loved beautiful gardens. His horticulturists grew a white tulip in one of the gardens. Nobles in the court had seen the tulip and they also began growing their own tulips. Images of the white tulip were woven into rugs and fired into ceramics. Suleiman is credited with large-scale cultivation of the tulip and it is thought that the tulips spread throughout Europe because of Suleiman.

9. Death: On the 6th of September 1566, Suleiman, who had set out from Constantinople to command an expedition to Hungary, died, shortly before an Ottoman victory at the Siege of Szigetvár in Hungary. He was 71 years old.

10. Legacy: Sultan Suleiman and his close circle left a great legacy to Istanbul. Large mosques, baths and mausoleums were built. An architectural genius named Mimar Sinan became the palace architect in the 16th century. He added a new dimension to Ottoman architecture. Architectural development in this period continued after Suleiman’s death. Mimar Sinan also served during the reign of Suleiman’s son, Selim II and his grandson Murad III. Sinan built the Selimiye Mosque in Edirne, (formerly Adrianople) at the peak of his creative powers.

Kobo Daishi (Kukai), via Tricycle Buddhist Review

Kobo Daishi (Kukai), via Tricycle Buddhist Review Portrait of

Portrait of  Statue of

Statue of  Danjō-garan, head temple of Shingon Buddhism, Mount Koya

Danjō-garan, head temple of Shingon Buddhism, Mount Koya Shikoku Henro (Shikoku Pilgramage)

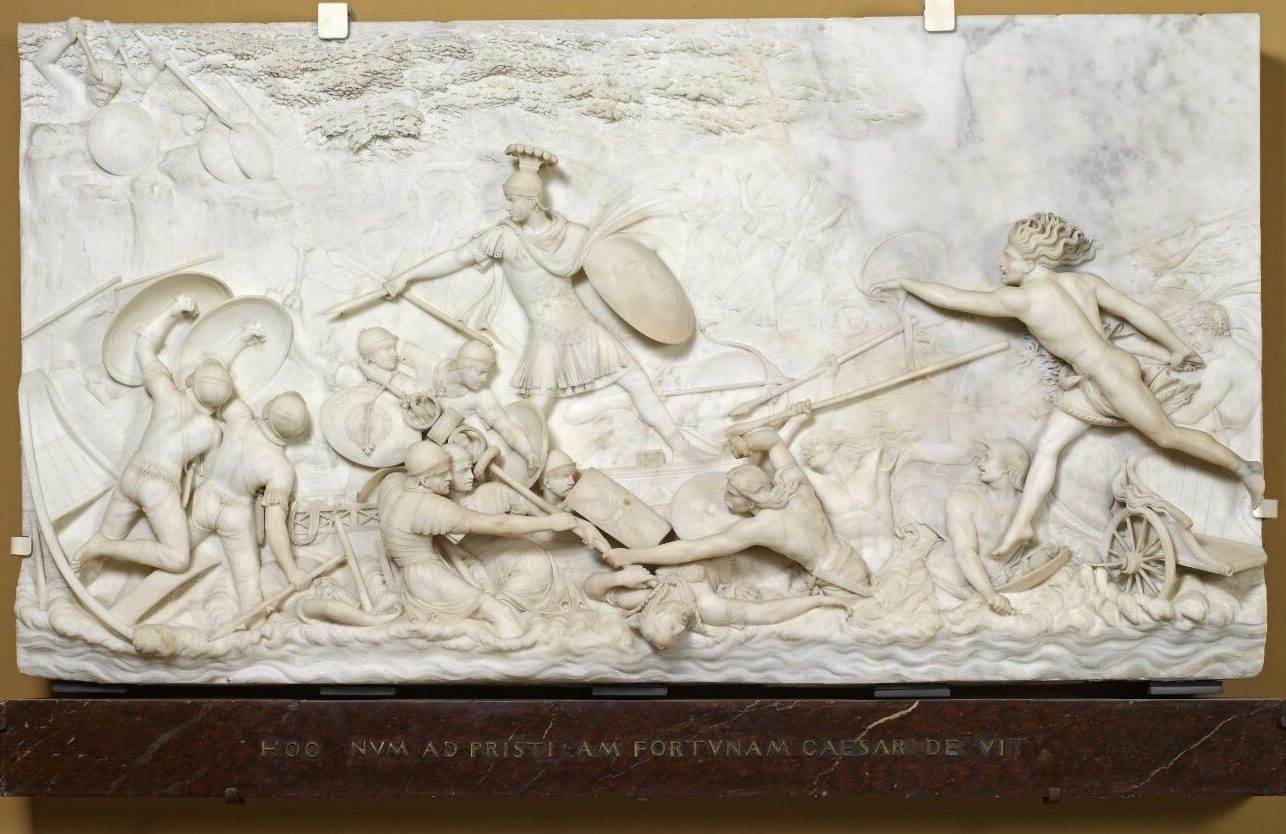

Shikoku Henro (Shikoku Pilgramage) John Deare’s marble relief of Caesar’s invasion of Britain, on display at the V&A, London

John Deare’s marble relief of Caesar’s invasion of Britain, on display at the V&A, London Print by William Sharp, from the engraving by Thomas Stothard, displayed at the National Portrait Gallery, London

Print by William Sharp, from the engraving by Thomas Stothard, displayed at the National Portrait Gallery, London

Hadrian’s Wall

Hadrian’s Wall Roman Baths in Bath, UK

Roman Baths in Bath, UK Photo credit, History Skills

Photo credit, History Skills