Our Strzelecki Tour takes us across the Great Dividing Range from the Pacific to the Southern Ocean and takes in Australia’s most iconic climbs. But who exactly was Strzelecki?

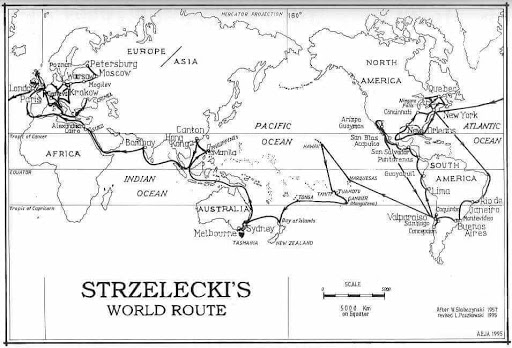

Sir Paul Edmund de Strzelecki, to give him his full title, was a Polish-born explorer, scientist and nobleman. Prior to landing in Australia in 1839, he’d briefly served in the Prussian Army, and was an experienced explorer with several expeditions under his belt. He initially set sail from Liverpool, England to New York in 1834, where he began an epic geological trip in the Americas, which included discovering copper in Canada, and travelling the west coast from Chile to California. He visited Cuba, Tahiti and the South Sea Islands before eventually arriving in Sydney.

With an ambitious dream of conducting a geological survey of Australia, Strzelecki’s expeditions would see him cover over 7,000 miles in New South Wales, Victoria and Tasmania. While studying the mineralogy of the country he was the first person to discover gold and silver near Hartley and Wellington, but Governor Gipps, in office at the time, asked him to keep his discovery a secret, to avoid a gold rush and to maintain discipline among the convict population. Strzelecki agreed, and in doing so apparently forfeited his own claim to a fortune.

His expedition led him through the Snowy Mountains, where he climbed the highest peak in Australia, naming it Mount Kosciuszko, after Polish leader Tadeusz Kosciuszko. Kosciuszko was a worthy namesake, considered a national hero not just in his native Poland, but also in Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine and the USA. He fought on the US side in the American Revolutionary War, and is honoured with statues in several US cities – to fight against the British and then have a mountain named after him in a British Colony is pretty impressive! If Strzelecki had marked his map with the local indigenous name of ‘Targangal’ however, Australians would have had a far easier time of spelling out their highest mountain for the last 160 years.

Strzelecki then travelled south through the area he named Gippsland, after the Governor. After passing the la Trobe River things took a turn for the worse and the party were forced to abandon the horses and minerals and make a dash for Melbourne. They reached it on the edge of starvation and exhaustion, but thankfully alive, in May 1840.

He was accompanied on his trip by James Macarthur and James Riley, and it was mainly thanks to their Aboriginal guides Charlie Tarra and Jackey that the group survived. Cycling trivia fans might be interested to note that James Riley was the great-grandfather of one of Australia’s greatest cyclists, Russell Mockridge. Mockridge won cycling medals around the world, and even beat the pros in Paris in 1952 – a ‘humiliation’ which caused organisers to ban amateurs for years. He competed in the 1952 Olympics in Helsinki, turned pro the following year, and was one of only 60 riders to finish the 1955 Tour de France, out of a starting line of 150.

Strzelecki then travelled Tasmania (or Van Diemen’s Land as it was then known) for two years, discovering coal while he was there, before returning to Australia. He eventually set sail back to England in 1843, managing to squeeze in further expeditions in China, the East Indies and Egypt on his way back. On his return he published his findings to great acclaim from the scientific community. His snappily-titled Physical Description of New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land won him praise from Charles Darwin himself, and was awarded the Gold Medal of the Royal Geographical Society.

He produced the first large geological map of New South Wales and Tasmania, which is still on public display at the Royal Geographical Society in London. He later became a British Citizen, and in 1869 was knighted, receiving the title of Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George (KCMG), an honour specifically for services to the British Commonwealth, most notably his work done as a famine relief agent, which he refused to accept payment for and it has been estimated that the various works in which he was involved in during those horrible famine years saved 200,000 lives.